In an interview in December 2020, journalist Richard Gutjahr asked the president of the Bavarian data protection supervisory authority, Michael Will, to reject all trackers on the Süddeutsche Zeitung website as a test. The supervisor failed spectacularly because he allowed himself to be led astray by “dark patterns” in the SZ’s consent banner. Believing in good faith that he had denied consent for all trackers, he overlooked a subpage on which he should have additionally “deactivated” the legitimate interest for these trackers.

Richard Gutjahr’s conversation with Michael Will

It’s not uncommon for consent tools not to do what they say they do. However, the Süddeutsche Zeitung and the manufacturer of its consent tool (the US company Sourcepoint) did not in any way come up with the confusing user guidance in the case described here – they rather, like practically all European online media, adhere to a precisely defined standard , the “ Transparency & Consent Framework (TCF) ”, an initiative of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Europe. The latter monitors compliance and threatens non-conformists with exclusion and thus sensitive sales losses.

The IAB Europe is the European arm of the IAB, an international trade association of the online advertising industry with 650 members. In Germany, it primarily represents the interests of the publishing and media industry, as the Online Marketing Group in the German Digital Economy Association is the representative for Germany in IAB Europe.

With the TCF, the IAB Europe has achieved a stroke of genius. Not only has it sworn the entire industry, including such heavyweights as Google, to a common approach, it has so far also been able to prevent the business model of its members, which is acutely endangered by DSGVO and ePrivacy, from being stripped of its legitimacy. How has it been able to do so?

“The Biggest Data Breach Ever”

In Europe, the digital advertising ecosystem is based almost exclusively on display advertising, as there are no significant European players in the field of social media and search engines. Banner advertising is the main source of income for all online media; money can only be earned to a very limited extent with content subscription models. In Germany , sales of display advertising amounted to €5.1 billion in 2021 .

Anyone who says display advertising today actually means “programmatic advertising”, also known as “real time bidding” (RTB), because 80% of the display advertising market is accounted for by this method of ad placement.

With RTB, publishers’ ad inventory is auctioned off to the highest bidder via a complex technical infrastructure, while at the same time targeting based on profiling is common. From the perspective of the media industry, this may be an understandable necessity, but data protection activists criticize the extent to which users’ informational self-determination is regularly violated in RTB – because sensitive user profiles are passed on to a large number of companies as part of the auction.

In a complaint to the Irish Data Protection Authority, Johnny Ryan, a member of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties and a former employee of the browser manufacturer Brave, describes the RTB as ” the largest known data protection breach of all time “. He cites as an example that data brokers offered personalized advertising to users from categories such as “brain tumor”, “depression” or “incontinence”. This development is also a thorn in the side of politicians. Tiemo Wölken (SPD), member of the European Parliament, is even calling for a ban on personalized advertising, for example.

JohnnyRyan

As a result, data protection regulations such as DSGVO and ePrivacy reform pose an acute threat to the RTB business model. IAB Europe’s lobbying efforts are correspondingly massive: member companies are not only involved in Brussels, where 15,000 lobbyists are said to be bustling about, but also exert influence via national ministries.

Apparently, the GDPR legal basis of “legitimate interest” also goes back to successful lobbying. In an interview with Richard Gutjahr, MEP Tiemo Wölken describes how this was incorporated into the GDPR as a compromise formulation in order to resolve a stalemate in the EU Council of Ministers and to make the GDPR possible in the first place. Consequently, a position paper by the German federal government on ePrivacy regulation also refers to this and introduces the term “legitimate business models” (“ they must not preclude the development and use of legitimate business models; this notably applies to business models that ensure access to information that is influential on user’s opinion “)

Introduction of the TCF – the advertising industry reacts

Just in time for the GDPR coming into force in May 2018, IAB Europe, together with its subsidiary IAB Tech Lab, presented a specification for a standard that was intended to create the seemingly impossible balancing act between conformity with the GDPR and securing the RTB business model. Since the use of consent tools seemed unavoidable in the future, the draft envisaged a design for these platforms that would cause as little pain as possible to the advertising industry. The Transparency & Consent Framework was updated with version 2.0 in October 2020, at which time Google also joined with its advertising marketplace “Ad Manager”.

The TCF standard largely defines how compliant consent tools must look and behave, as well as the interaction between the media companies (“publishers”), the consent tools (“CMPs”) and the players in the RTB business (“Vendors”) regulated. A document from the IAB describes these “policies” on almost 70 PDF pages. All major manufacturers of consent tools have been certified for the standard and offer their products in a TCF-compliant mode in addition to the “normal” functionality. This is manifested in the following aspects, among others.

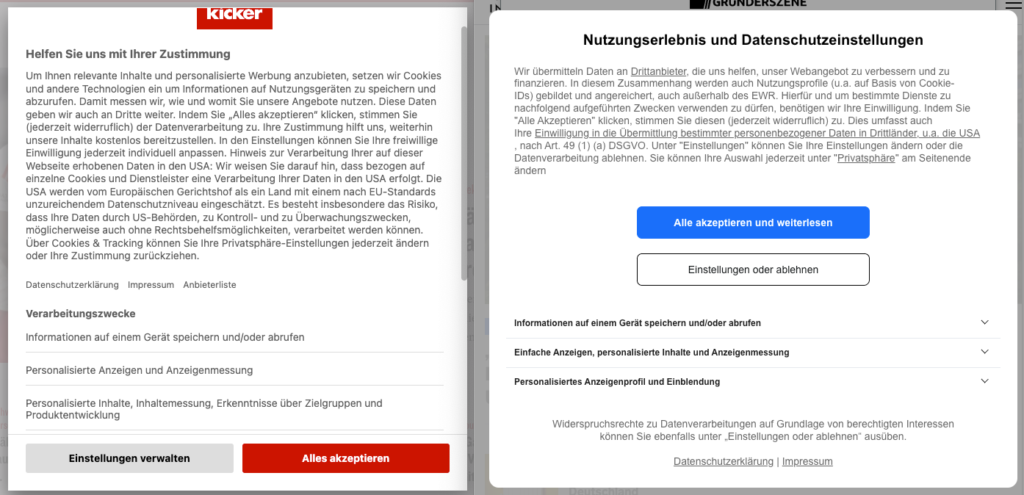

Two typical TCF banners

Precisely defined uses

The TCF envisions that visitor consents are not simply obtained for the use of a service, but rather that each service specifies the purposes for which it wishes to process data from a fixed list, such as “Create a personalized ad profile.” In fact, the framework does not simply provide for “Purposes”, but additionally for “Special Purposes”, “Features” and “Special Features”. Here, Special Purposes do not require consent from the Framework’s perspective (such as “Ensure security, prevent fraud, and fix bugs”), while Features and Special Features are supporting technical measures, such as “Use accurate location data.”

The specification also leaves little question as to how this information is presented and how it can be selected in the Consent Tool. The exact names and explanatory texts of all purposes are available as translations in 35 languages, and even the possibility of grouping the Purposes into so-called “stacks” is precisely defined. The form in which all this is listed on the overview page of the Consent Tool, and other pages below it, is specified by the standard, and conformity can be checked with the aid of validator software together with the associated checklist.

A button for refusing all consents at a click is not prohibited according to the specification, but is not even mentioned. Only when the tool is subsequently opened must a button be available that makes it possible to “withdraw consent as easily as it was given”. Consequently, TCF-compliant consent tools practically never have a button to withdraw all consents at once.

As a result, a TCF-compliant consent tool is already visually immediately recognizable as such.

Recourse to “legitimate interest”

The inventors of the TCF framework apparently had – presumably justified – doubts that participants in Programmatic Advertising could collect and exploit sufficient user data if voluntary and informed consent was a prerequisite in each individual case. Therefore, the legal basis of “legitimate interest” pursuant to Article 6 (1)(f) of the GDPR was integrated as a central element. A vendor can therefore choose for itself which legal basis it wishes to use to process data for the specified purposes – consent or legitimate interest. If the vendor chooses legitimate interest as the legal basis, the user must actively object to the processing; consent that has not been given is not sufficient. In addition, the specification specifies that this objection option must be offered on a sub-page.

This aspect in particular is often brought up as a point of criticism (see below).

relinquishment of control functions

Consent tools usually technically implement consent to the processing of data by an external service by allowing the web browser to load the service through network access (or instructing a tag manager to load the service accordingly). Only then does the service have the ability to set cookies and build user profiles. Conversely, if consent is denied, loading of the service is blocked.

Given the complex structuring of purposes described above, as well as the nature of real-time bidding, the TCF standard provides for a different procedure: the user’s use of the consent tool creates a comprehensive data set that describes exactly which advertising company is allowed to use his data and for what purposes. This data set is stored as a so-called “consent string” in a cookie and distributed to the parties involved in the RTB bidding process. Whether the vendors actually adhere to the specifications and, for example, refrain from setting cookies or retrieving location data, can no longer be monitored.

Criticism of the TCF standard

According to IAB Europe, the TCF framework “empowers consumers to give or withhold consent, and to exercise their right to object to data processing.” It goes even further, writing “Consumers also gain more control over whether and how vendors may use certain features of data processing, for example, the use of precise geolocation.”

European privacy activists and legal scholars are far from convinced, and have been criticizing Real Time Bidding in general and the TCF framework in particular for years.

The investigations by Nataliia Bielova, Cristiana Santos and Celestin Matte from the French INRIA Institute deserve special mention here. The research team examined the uses and the use of the legal basis “legitimate interest” in the TCF standard and concluded that the standard largely contravenes the GDPR and ePrivacy Directive. For example, intended uses of the TCF such as “developing and improving products” are not legal because they sound understandable at first, but unlike what is required by the GDPR, they are not specific and unambiguous, so a legal basis cannot be derived at all. In contrast to the TCF standard, the researchers also consider consent to be mandatory for all but two uses of the TCF. In their publication, the research trio expresses the hope “that these studies will prove useful for lawmakers,

The framework first encountered backlash from a regulator in October 2020 when the Belgian Data Protection Authority (APD-GBA) began a formal investigation into the TCF standard , apparently in response to a series of complaints led by the Irish Council for Civil Liberties submitted by Johnny Ryan to several European regulators. According to the Council, the agency found that “IAB Europe’s approach shows that the risks affecting the rights and freedoms of those affected are neglected”.

IAB Europe promptly responded with a statement denying all allegations. Whether or not data processing would happen on the basis of legitimate interest is solely the decision of the users of the TCF, the IAB does not give any direction here, it said. And although some supervisory authorities were critical of profiling on the basis of legitimate interest, it was not prohibited by the GDPR.

A result of the investigation was announced for spring 2021, and at the beginning of November 2021, there was finally movement in the process: in a press release, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties boldly announced “We have won.” In a draft decision, the Belgian data protection regulator found that the TCF framework violates the GDPR and is therefore illegal. In addition, the IAB is seen as a controller in the sense of the GDPR, namely for the processing of the so-called “consent string” with the stored user consents. Meanwhile, the IAB Europe spread purposeful optimism in its own statement: “We look forward to the outcome of the Cooperation Procedure and stand ready to work with the APD and other DPAs to support companies in the digital advertising industry to ensure that they fully comply with the requirements of EU law.” It also filed an appeal with the Belgian Market Court.

The data protection association NOYB (“None of your Business”), led by Max Schrems, also took action against the TCF framework. In December 2019, the association filed a complaint with the French data protection regulator CNIL, referring to the Inria researchers’ investigation. In it, IAB Europe was accused of producing “fake consents.” Formal complaints followed in May 2021 and August 2022, criticizing the advertising industry for the use of “dark patterns” in its consent banners, particularly regarding the lack of an easy-to-find opt-out function. IAB Europe responded to this as well, saying that the TCF Framework provides a minimum standard, that European authorities disagree on how to assess these practices, and that the ultimate responsibility lies with the participants in the RTB process.

What’s next?

The business model of programmatic advertising and the “Transparency and Consent Framework” standard that legitimizes it have so far proven to be surprisingly robust, even though the criticisms put forward by data protectionists seem more than valid.

With regard to the findings of the Belgian data protection authority APD, it has now confirmed that it will await the decision of the Market Court, which is expected in September 2022 at the earliest. If the IAB’s appeal is then rejected, the TCF standard would have to be converted into a compliant form within 6 months. So it remains exciting.